This week I’ve been thinking a lot about world building and I’ve started to build out a framework for fantasy setting building that I think might be helpful for other writers and creators. Before we get too deep into the details, let’s just state the basic concept.

The major question at play is when your setting happens in relation to existing, known, and important world events. I propose that, at a high level, there are four major types of fantasy setting: pre-fantasy, post-fantasy, middle-fantasy and Iso-fantasy.

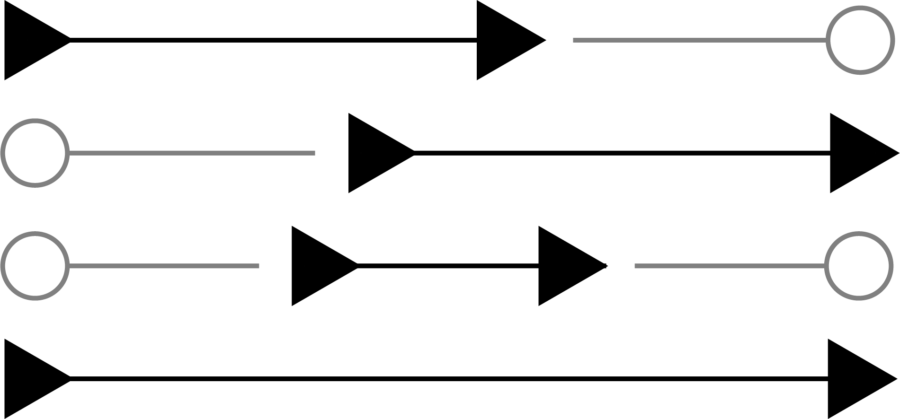

- Pre-fantasy: happens before an important, known world event.

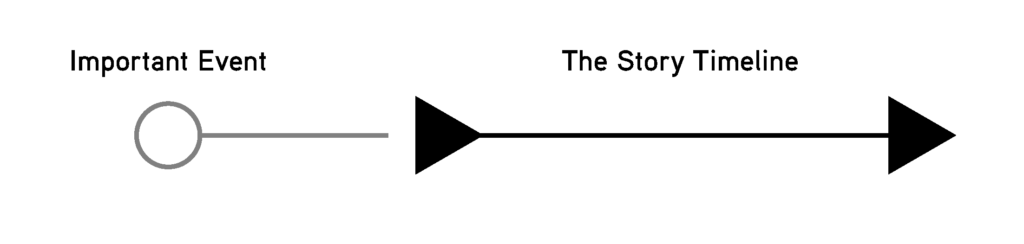

- Post-fantasy: happens after an important world event.

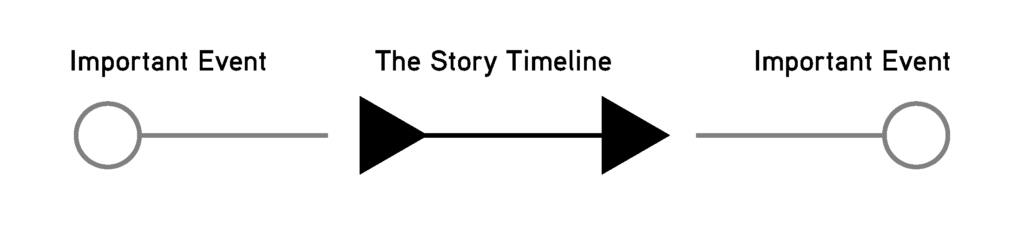

- Mid-fantasy: happens in-between two important world events.

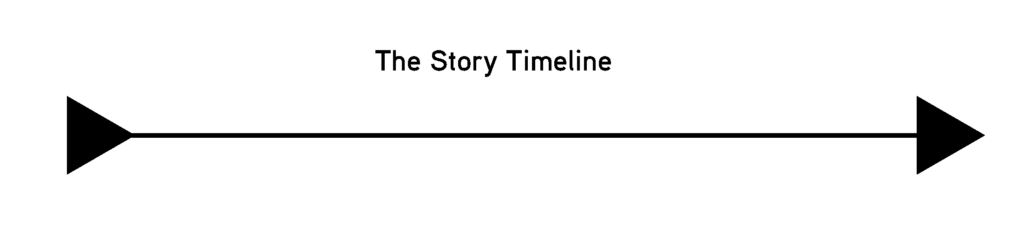

- Iso-fantasy: (short for isolated) is not defined in relationship to another known world event.

Now that we have a very high level understanding of these worldbuilding buckets. Let’s take a look at some examples, the pros and cons of each category, and and the effect they might have upon your story.

Pre-Fantasy

Pre-fantasy happens before an important world event. Say, for example you have a fantasy setting in which a young jewish girl in Germany discovers fairies in 1937. This setting is obviously going to be greatly tinged by events that we know are about to happen. Perhaps you have a theme of the loss of innocence, the end of magic, and the entrance to adulthood. You can see how the audience’s fore-knowledge of coming events filters and changes the flavor of the world.

Another way that pre-fantasy is used is as a setting that simply happens before the normal historical timeline. Arthurian legends, with elements of magic and sorcery, are often crafted in a way that conveys the idea that the world once contained magic, that before the world was drab, there was a time of legends. Are you catching a theme here? Pre-fantasy is excellent at instilling feelings of ennui and nostalgia.

A great example of a pre-fantasy is Hayao Miyazaki’s Princess Mononoke, which is set in a mythical pre-modern Japan. Magical elements are dying out and the world is becoming more like the modern world. The story about the death of the forest spirit is enhanced by the audience’s knowledge that modern times without magic will inevitably come.

Post-Fantasy

Post-Fantasy is perhaps the most intuitive of the world-building flavors because it is so prevalent. Post apocalyptic tales like Mad Max or Jeff Vandermeer’s bio-punk Borne, happen after a world shattering event, their setting is defined by it! But post-fantasy doesn’t have to be post-apocalyptic. Scott Lynch’s The Lies of Locke Lamora is set in a Venice inspired renaissance era fantasy. Why does it count as post-fantasy? Lynch uses ancient ruins built by a powerful civilization to give his world a sense of history and depth. Post fantasies can be set in the future or the past. It’s not about the setting’s relationship to the current time, it’s about the setting’s relationship to other known world events. Steam, punk, for example, can generally be considered post-fantasy in that it takes the known period of the 1800’s and extrapolates forward on an alternative timeline. Almost all sci-fi is post-fantasy for this reason unless it’s setting is highly defined by events that are yet to come.

Mid-Fantasy

Okay, by now I’m sure you’re getting the hang of the idea and can probably make some guesses about what mid-fantasy might be. The primary example of this is Tolkein’s Lord of the Rings, he even calls it middle earth!

The setting of LOTR happens after a period of known mythology; important, world building events. However, the setting simultaneously implies that the “age of man” is coming. A creative read into the setting might imply, that as in pre-fantasy, the age of magic is coming to an end. The ents and elves are leaving. One can imagine a smooth transition from this mythical time into an essentially medieval, real-world timeline. What does this do for Tolkien? This instills that sense of longing, ennui and sorrow into his setting while simultaneously benefitting from the deep history that preceded it.

Iso-Fantasy

Iso-Fantasy is a story timeline that is isolated from important world events. Many stories fall into this category. This doesn’t mean that important events haven’t happened in that world, simply that they haven’t inherently defined the flavor of the setting. Let’s take a super hero film as an example, Into the Spider Verse. It’s a great film with fantastical elements, but the world doesn’t have to exist in relationship to a post-apocalypse or an alternate timeline and it doesn’t have to precede anything. It simply is what it is. You might note, however, that iso-fantasy settings don’t benefit as strongly from the deep histories of post-fantasies and they don’t carry the emotional ennui of pre-fantasies. That doesn’t mean that the story itself can’t contain those elements, or that the worldbuilding can’t achieve this through other means.

And there you have it! Four distinct flavors of worldbuilding. If you’re working in speculative fiction, your project likely already falls into one of these categories. Lean into the strengths of your flavor, build the world intentionally, and you can create a compelling world that keeps your audience interested and lingers in their brain for many years to come.